Plays mentioned: Romeo and Juliet, Macbeth, Henry V, Twelfth Night, As You Like It, A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Some Twelfth Night spoilers.

Let me guess. When you were in high school English class, you read Macbeth and Romeo and Juliet? Maybe you had King Lear sprinkled in there, or Hamlet or, if you were lucky, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, but you definitely read Macbeth and Romeo and Juliet. There is a range of reactions to Shakespeare, from indifference to elation, annoyance to enjoyment, and, since his work is such a pillar of our high school reading lists, it is worth asking the question: is he worth it?

The short answer is yes.

I have my reasons. In fact, I even understand why the two abovementioned plays are such constants on the syllabus, but I think the main reason we read Shakespeare is because he really is that good. Why we might not get as much enjoyment out of Shakespeare as we possibly could when we’re in high school is because of how it’s taught.

There are two extremes to misinterpreting Shakespeare and those are: missing out on his brilliant sense of humor, and completely reducing him to his brilliant sense of humor. The latter camp mostly exists, as far as I know, through memes on the internet about how Shakespeare is just “1,000 dick jokes strung together by an increasingly ridiculous plot”. (Note: I have a sense of humor. I understand that memes are jokes. I just want to give as broad a look at the topic as possible). It is irreverent teens rolling their eyes at their teacher “over-analyzing” the Bard, claiming he would have laughed himself out of his grave if he knew how seriously his plays are taken. The former is best encapsulated by the Laurence Olivier style of reciting lines, where Shakespeare is read like poetry and the clever turn of phrase is often smoothed over in a drone of prettily read monologue.

The major problem with the first side of the argument is that it completely eliminates the skillful balancing act that is a Shakespearian play. I mean, the man isn’t just puns and raunchiness; he is puns and raunchiness and universal characters and somehow keeping a running motif while working exclusively in iambic pentameter for that section. The problem with the second is that the lines lose their literal meaning and clarity. Shakespeare becomes inaccessible, any fun or playfulness quashed. The brilliance of Shakespeare is that he is both: irreverent and serious, funny and meaningful. A pun can be both a funny joke and a clever usage of language and theming.

“All the world’s a stage//And all the men and women merely players” from As You Like It. Is “the world” a play on the fact that the theatre where Shakespeare put his plays on was called “The Globe”? Yes, likely. Is it also an interesting obversation about the fourth walls of theatre, calling into question where play-acting ends and reality starts? Also, yes. One does not cancel out the other. If anything, they strengthen each other, the pun drawing the present audience in.

Now that I’ve finished the mandated “analyzing Shakespeare lines” portion of this commentary on Shakespeare, I can move on to how this plays into the high school curriculum. In short, I think Shakespeare is a lot more approachable than we give him credit. He didn’t write exclusively for a uniquely educated aristocratic class, making inside jokes no one outside of a specific social stratus of Elizabethan England could ever hope to understand. He wrote for the masses, for everyone.

Why I think Macbeth is a good play for the high school curriculum

- I’m pretty sure I’ve made this point in every piece so far but, it’s short. I don’t think I can stress how helpful it is when literature is short in high school. At age 16, I was balancing 14 classes. I was much more likely to carefully read a play that was less than 2,500 lines than one that was over 4,000 (looking at you, Hamlet).

- It has witches. Witches are awesome.

- It has ghosts. Ghost are awesome. Really, what I’m saying is its supernatural elements make it an engaging read. There is a lot of plot in Macbeth so the actual story pace is gripping… as long as you don’t have expansive, rolling shots of Scottish wilderness sprinkled constantly throughout (looking at you, 2015 Kurzel adaptation of Macbeth)

- The themes are clear and at the forefront of the play. I’ll use an example. One of the themes of Macbeth is ambition. This can be seen clearly not only in the actions of the protagonist but in side characters, in monologues, in dialogue, in the way the plot actually develops. You can always dig deeper for more nuance, but this specific play generally has a clear entrance point.

- Lady Macbeth is one of the best Shakespeare characters out there. The most Slytherin to ever Slytherin. Imagine every deliciously cunning, brutally ambitious character out there. This is their mother. Really, if you haven’t read the play, just read it. It is my favorite Shakespeare play.

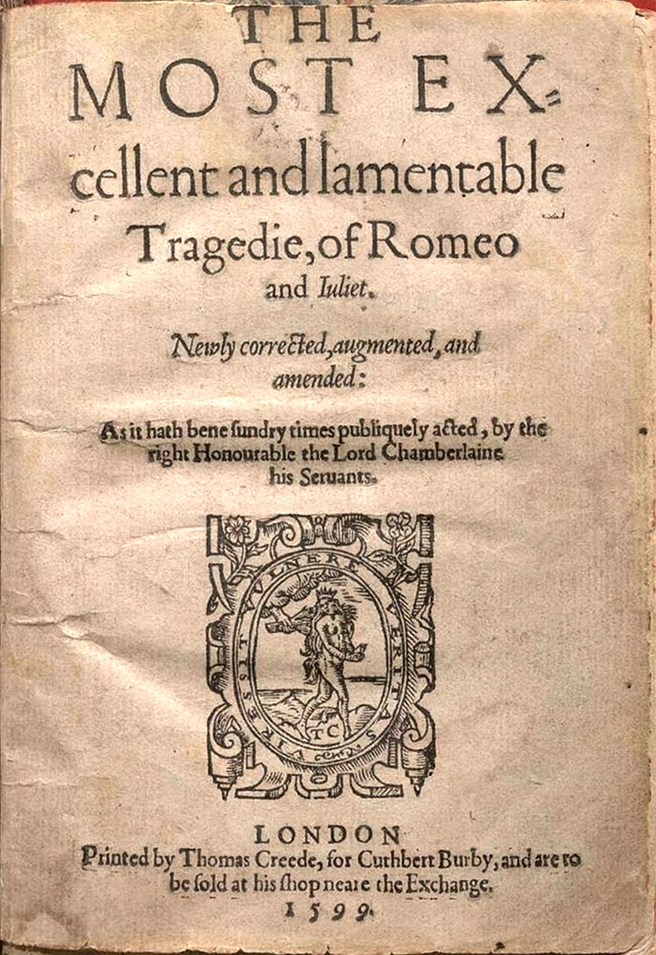

Why I think Romeo and Juliet is good for the high school curriculum

- It stars teenagers. If the wild popularity of YA has proven anything, it is that teens like to read about teens.

- Again, it has clear theming. Romeo and Juliet has the extra bonus point of being part of the cultural conciousness. You don’t usually approach it without some idea about it, its plots, its themes. You may have already watched an adaptation based on it, like West Side Story or Lion King 2: Simba’s Pride. Having a starting point is always helpful.

- Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet exists. Okay, this point is half a joke, but it does link into a discussion I wanted to have so bear with. Also, this specific adaptation contains the best version of the “do you bite your thumb?” scene out there, really captures the chaos, and Harold Perrineau is perfect as Mercutio.

You may have noticed that adaptations have come up a lot in this essay (blog post? researched internet rant?). That is because I think the biggest mistake you can make when approaching Shakespeare (and most plays really) is to just read them. Technically, they aren’t meant to be read. They’re meant to be watched, or performed. I don’t think the high school curriculum puts enough emphasis on the watching part.

Shakespeare’s language is difficult. Like I said above, the man loved to pun, but he also loved to engage in such fun actions as: literally inventing words, messing with syntax to make his point more emphatic, relying on a vocabulary from the 1600s. All of this can be so alienating to a new reader. All of this can still be alienating to an experienced reader. It can be so easy to forget that these are words that are meant to be said by actual people, to get lost in the rhyme and rhythym and forget that they are supposed to convey emotion. To focus so heavily on the symbolic reading that you forget there is also a literal interpretation.

(Side note, The Toast’s “Dirtbag” Shakespeare series does a perfect job of striking a balance between treating Shakespeare with the reverence of an anarchic teen at a student council rally, and having a really good understanding of what Shakespeare is trying to get at)

A lot of this is solved when you get to see a Shakespeare play. The actors in it have poured over this work, have done their side of the analytical burden, and are able to produce a closer version of the way the words are meant to sound. Yes, it is important for high school students to also read the plays and be able to mark their own interpretations, but when done without the counterpart, without the performance, the works lose their resonance and their humanity. My first recommendation to someone who says they don’t like Shakespeare is to tell them to go see a play. It serves as a good reminder that Shakespeare is funny, is tragic, is actually pretty good at creating complex human characters that also serve as explorations of nuanced themes. Plays were not made to be read, they were made to be interpreted.

As a final point, while I understand why Romeo and Juliet and Macbeth make it onto the curriculum, I don’t necessarily think they are the best options either. The themes in Macbeth, for instance, aren’t quite so personally relatable to high school students. They won’t find themselves in a position to seize power over Scotland anytime in the near future, probably. Romeo and Juliet is a bit better, high schoolers have likely have had a crush before where they feel like if they don’t do something about it they will die, but sometimes the play’s existence in the cultural conciousness is to its own detriment. You might be sick of hearing about it before you even get to it. So, my suggestion is to bring in a play that is fresher, with themes that might be slightly more relevant to today’s modern identity-politics-oriented world: Twelfth Night.

For one thing (and this is my last point about adaptation), it would mean you can justify watching She’s the Man for school. For another, it is a play all about liminality, about pushing the limits of what is societally acceptable, questioning why things count as societally acceptable; it is about performance of the self. That is, these are themes that could resonate closely with teens’ actual experiences, even if they’ve never had to dress up as their twin brother to help the Duke get with a lady who is totally into them instead while starting to think the Duke is looking pretty fine. Also, the play is funny. I emphasized the importance of performance earlier. Twelfth Night opens itself to the possibility of being read aloud in class, of being truly enjoyed. As someone who was in and watched many classroom interpretations of a selection of scenes from Romeo and Juliet, I can say it is easy to tune out. None of us are professional actors and it is easy to fall into the whole “reading Shakespeare as poetry” act, which is (potentially scandalous claim) neither fun to watch nor act. You know what the most engaged I’ve ever seen a classroom in Shakespeare is? When a friend (who is, in fact, much shorter than me) and I read out, not even acted just read aloud, the scene in A Midsummer Night’s Dream where Helena and Hermia fight and most of it consists of Helena basically finding creative ways of calling Hermia short and Hermia getting really mad about it. It is easier to find a quick way to engage with comedy; all you need to do is laugh and you’re in. You’re involved.

(Note: I suggest Twelfth Night instead of Midsummer Night’s Dream because I think its use of drag opens the possible discussion of gender and gender presentation, and further of identity, in a way that could be really interesting to link to modern sensibilities).

In short, I think Twelfth Night is a play high schoolers could have a lot of fun with while also finding in it relatable themes, topics to identify with. It is easier to put on a successful amateur adaptation of a scene from this play than, say, from Romeo and Juliet because a lot of the comedy can be physical: characters disguised as other characters and the dramatic irony that ensues. Everyone is passionately in love, except no one really knows to whom (except Angelo, who totally knows what he is about). Like I said, the laughter is a way in. And that, I think, is what is often missing when introducing teens to Shakespeare. A way of getting their foot in the door.